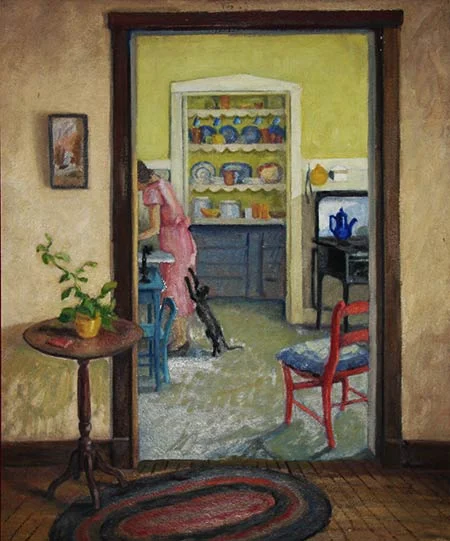

The painting sits above two bookshelves in our living room, sandwiched between a purple potted orchid named Sven and an old Bell and Howell film projector. Every morning, sitting at the kitchen table, it catches my eye. Four years ago, it arrived in a large unmarked box from my wife's father and stepmother. They volunteer at a thrift shop in Cape Coral, Florida, and often surprise us with antique cameras, clocks, and other bric-a-brac that mesh with our penchant for hand-worn technology. After shoveling through a swath of bubble wrap and styrofoam peanuts, we found a handwritten note regarding the painting: it was titled "The Philosopher's Wife."

For a few weeks, it sat leaning against the wall with a set of unused picture frames. We weren't quite sure what to make of it, or even if we liked it. It seemed so plainspoken, in a homespun American style that had no congruity whatsoever with our artistic sensibilities. The way the painter chose to leave the scene in medias res, the woman's face completely out of view yet her body showing focused intent, the half-askew placemat in the foreground, the cupboard with dishes arrayed in a perfectly measured form: each element is mindfully arranged and yet completely bare of explicit meaning.

After yoga, eating breakfast slowly, I would stare at it, pretending I knew what was happening in the world within the painting:

The philosopher's wife was washing the dishes, luxuriating in the feel of their chipped bone china beneath her soap-soaked hands. Nothing else was in her mind except the mindful task of washing. She was so tired of those late nights, her husband with his wire-rimmed glasses, lost in the complete works of Wittgenstein. She would finish the dishes before she fed the cat for what seemed like the eighth time that day, change into something a little more presentable, and leave home to buy the week's groceries.

Or, another morning's story:

Her husband has just left to work at the university. He had been sitting in the red chair, which he'd dragged from the dining room. While she was kneading dough for biscuits, he was explaining to her the filigree of an idea from Plato. As she was rolling the dough out onto a floured board, she imagined that her makeshift Mason jar would make each dough become "a biscuit." The paws of her black cat against her dress, begging. Her food bowl was empty. Again. Why couldn't she just feed herself?

And so on, for many weeks, it seemed that I would never run out of stories, but none of them seemed particularly satisfying, and I couldn't figure out why. Many years later, I feel like I might have the vague shape of an answer.

This painting shows things exactly as they are for the viewer. After I eat breakfast, I take my bowl over to the sink, lean over to wash it, and if I had a cat, it would look up at me intently, hoping that I would feed it before heading off to work. Even while the philosopher is off discovering through reason the inner workings of existence, the dishes still need to get done.

It's a strange sort of American Zen, this painting. It is everything and nothing, all at once. This is a kind of feeling I've wanted to express through both my personal work and design for some time, and repeatedly failed. It may have to do with the root of not what design is, but how it's currently applied in today's corporate culture. Design may make such realities more bearable, but it rarely reflects directly the nature of things "as they are," unless you work with nonprofit clients who are combatting serious atrocities that must be confronted in their barest essence.

Being a professional form-maker — one who looks to enclose an idea in a tangible construction or artifact for a paying client — is wearying for anyone who seeks to provide their audience with this kind of directness of meaning. The domain of the artist is often without a fixed meaning or limit, just like life. Most projects we designers are asked to complete are about limiting choice, striking one or two chords in a layout, editing the copy to promote a particular kind of focused desire and action. Pain = problem. Product = solution. End of story, begin new chapter in a never-ending hero's journey.

Much of what we produce in design school and as personal projects are able to walk this line between artifact and art much more successfully than any corporate project. Not so much in the agency world. This began to be painful after my first few years at a 120-person shop. "You don't need to take every detail so seriously," one creative director told me when he saw how I was trying to squeeze yet another metaphor into an already obtuse and belabored logo. "When you're creating a good design, it doesn't always have to mean something. It doesn't have to feel real." And by extension, she went on to note that I couldn't control every meaning that people would get out of a design anyways, that we were creating a product with a consistent meaning (versus art), we had a deadline to meet, and so forth.

That answer was good enough for a few years. It isn't anymore.

I yearn for that rhizome of meaning that, like a stalk of bamboo, continues to reassert itself no matter how many times you try to tear it from the earth. I think any designer who crossed into design from fine art understands the dilution that occurs to an artistic impulse when it crosses from an illustrative or photographic medium to a corporate product. Putting a Jackson Pollack painting alongside the Starbucks logo is like comparing a farm-fresh, tart apple to a glass of orange juice from concentrate. I want the apple core for my compost bin, not the empty glass in the sink.

When I look at "The Philosopher's Wife," and savor on my tongue the very conceit of its title, I am reminded that there is little philosophy in my trade except in our schooling. And while I am compensated well for creating artifacts for the service of commerce, I will always be tailoring last-year's fashions for entities that don't exist except in the mind. I call up Coca-Cola and talk to a representative of an idea of an organization that consists of people making things that we purchase so that they can get paid and we can ease a need or improve a life (hopefully). (Don't talk to Bear Stearns or WaMu and ask them what their company was made of. Depending on the product, your client organization may be as substantial as the weather.)

This puts a certain kind of strain on the creator of said artifacts. These works need to come from a human place, then be shaped to fit a corporeal need that is gone — much like life — in a whiff of smoke. Why should the ability to fix a moment in time through design, to make an artifact that actually transcends this moment and sticks to the wall for longer than a month or a year, seems like a function of chance, not intent, in our industry? Corporate design is meant for sussing out the grain of insight that fuels the next sale, the fulfillment or creation of unmet need. Spend every day crafting these types of short-term illusions and try not to let them rose-tint your glasses in today's Web 9.0 world. Much of what we create is not necessary, and what is necessary may not require our services. Being able to acknowledge this to a client definitely puts a crazy spin on what, to them, seems like their daily life-or-death reality. But often it isn't. Other than eating, sleeping, managing bodily functions, and Facebook, what do we need, really?

This isn't to belittle what pays the rent. There are moments of real joy in the making, and clients with "game-changing" ideas that transcend the soaps and bath tissues of the world. But all too often, I find the most delight in the purest attempt at making, these rare moments where it is only our selves and the material at our disposal, the pencil and the blank page, our lives as the canvas.

And I may desperately need art in my life, but I still need to go do the dishes before I can begin cooking tonight's dinner. These daily moments are a careless luxury we return to, again and again. They are the true force that feeds design.