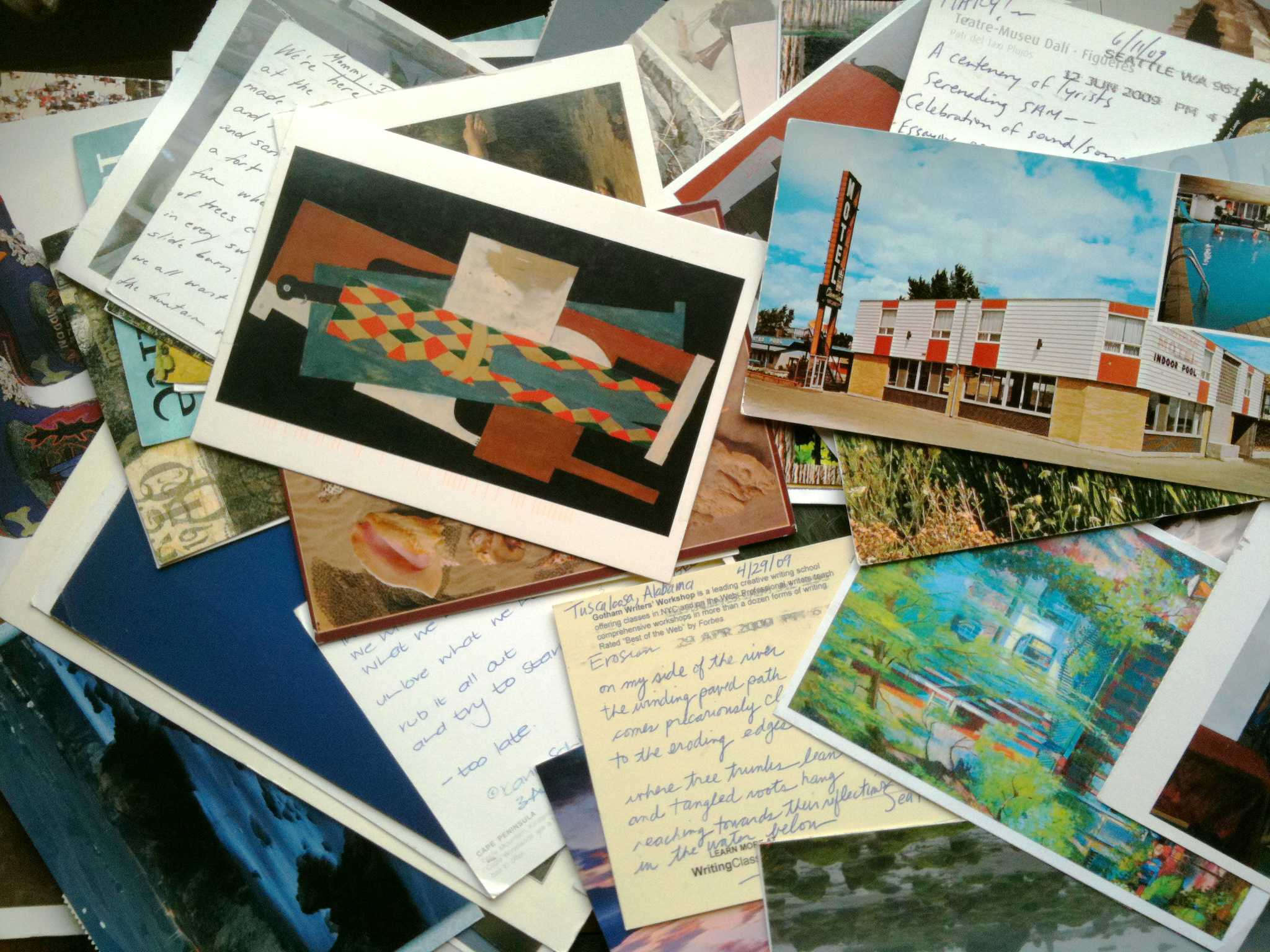

Something people with creative jobs always struggle with, myself included, is that creativity often likes to take its sweet damned time. We're forced into all sorts of habits and rituals that we feel will help us get to ideas more quickly. Totems of one such ritual sits on my desk: A pile of postcards at least three inches tall, sent from people all over the world. They serve as a reminder that creativity flows from well-considered constraint, married to daily discipline.

For example: here's one of "The Bean" in Chicago's Millennium Park, or a pink-purple sunrise over the wetlands of Hillman Marsh in Ontario, or a bald cypress tree at sunset in Louisiana. There are also many colorful landscapes of the mind: Andy Warhol's silkscreened "Four Monkeys," classic paintings by Matisse and Chagall and van Gogh, a lovely gouache happy face by the late designer Alan Fletcher. Postcards purchased from art museums and bookstores, or discovered in attics or at flea markets—often telling tales of places that no longer exist, whose history must be preserved through these yellowing squares of thick paperboard. Even rarer, I have a few that are hand-collaged together, oft painstakingly, from found type and image. One of my favorites, called "Bunny Love," is a treacly heart-shaped postcard made from purple and orange bits snipped from an Annie's cereal box.

Why do people send us so many postcards, of so many different persuasions? We are participants in August Poetry Postcard Fest — a writing experiment started by poets Paul Nelson and Lana Hechtman Ayers. Each postcard we receive contains a hand-composed poem, written and addressed to either me and my wife. In return for these gifts, she and I are responsible for writing and sending out a poem every day to a person on a provided list.

Sounds easy, right? There are a few additional constraints, however, which make the entire process challenging for anyone that suffers from Obsessive-Compulsive Design Disorder. This is from Lana's instructions for this year:

What to write? Something that relates to your sense of "place" however you interpret that, something about how you relate to the postcard image, what you see out the window, what you're reading, using a phrase/topic/or image from a card that you got, a dream you had that morning, or an image from it, etc. Like "real" postcards, get to something of the "here and now" when you write.

Now, that's a creative brief: be comfortable with capturing the mind as it is. Paul Nelson explains:

This project is an experiment in letting go of the need to be perfect and learn to train your mind to compose in the moment. Philip Whalen said his poetry was "a picture or graph of the mind moving."… This is the most difficult type of composition, as it very much reveals the quality of the poet's mind.

Seeing into the quality of your mind can often be scary, especially if the editorial impulse takes over. Since I work as a designer professionally — oft tasked with crafting moments that may hold the characteristics of art, but are polished and sharpened until they achieve a single-purposed sheen — this project went counter to almost every bone in my creative body. There was no second or fourteenth draft, and an assured audience of one, besides any curious post office workers.

This sense of being grounded in the moment of composition, and writing words directly into the postcard with a permanent tool (pencil, pen, typewriter), can be a real struggle for anyone used to waiting for inspiration to strike. Modern writing tools, like the computer, may provide some help, but there's too much risk that you'll spend time editing and crafting the material instead of letting it happen in the moment of composition. If you write a word or phrase you don't like, there's no going back unless you scrap the postcard and start anew.

Needless to say, my first year of participation was a struggle. Breaking the rules, I wrote ideas in my notebook first, then copied the material onto postcards. While this satisfied my desire to make sure I liked what I'd written before I sent it off, I was totally missing the point: the project isn't about writing great material, as it would be impossible to force out a satisfactory piece of art each day. (What does "satisfactory" mean, anyhow? Whom needs to be satisfied?)

The second year, however, I vowed to try and hold to the spirit of the project. After struggling through the first dozen postcards, I became more comfortable in placing raw, nascent thoughts on paper. By the twentieth card, I could quell the editor, always hovering with his red pen in my mind. But by the time I had finished out the month, I had learned how to capture a mental gesture organically, through words. I had also sensed something novel, which I hadn't been able (yet) to bring into my daily work as a designer: a sense of improvisation and play in the midst of ever-encroaching deadlines.

Isn't this where any innovation begins? A blank page, tied to a cleverly constrained problem that could be solved an almost infinite number of ways. Intuition lurks in the boundaries, defining the space where we can roam freely.

In this paradoxical duality is the key to unlocking almost any kind of creative challenge. Spending so much time writing postcards made me realize that the physical scale of the material we use to capture our thoughts has an impact on the quality and fidelity of ideas that we generate.

Post-It notes encourage describing the essence of an idea in just a few words or a micro-doodle. Postcards allow a few thoughts to weave together, suggesting further possibilities. A sheet of paper cut in half can fit a few detailed sketches. A full 8.5"x11" sheet feels positively luxurious, affording an almost overwhelming number of uses. Choosing between a pencil or a permanent marker can often feel less important than selecting the right size and shape of the "capture medium" for your ideas. Then, by repeatedly choosing those materials for those ideas creates habit fields, reinforcing and encouraging that type of output over time.

A web page or an open window in a word processing program provides endless space, for better or for worse. Sometimes, that amount of space is what a set of ideas requires to be brought, fully-formed and friction-free, into the world.

But with another year and another dozen postcards waiting to be completed, I'm going to keep focusing on how I can continue to sharpen my sense of the here and now, by intentionally using tools at the start of every important creative project that force a little bit of inefficiency. And with such constraint and force of habit, we receive access to the wellspring of any meaningful creative effort: our boundless intuition.